As a participant in the construction of custom, high-performance facades, Enclos finds itself on a handful of recent and upcoming supertalls, including 432 Park Avenue, which was the 100th supertall constructed in the world when it became the tallest residential tower in the western hemisphere upon completion in late 2015. Other supertalls completed in recent years with Enclos’ involvement include 30 Hudson Yards at 1268´ (386.6 m, 73 floors, 2019), 53W53 at 1050´ (320 m, 77 floors, 2018) and Comcast Technology Center at 1121 ft (341.7 m, 59 floors, 2018). 53W53, as well as 220 Central Park South – though just shy of supertall status at 950´ (289.6 m, 66 floors, 2018) – will join 432 Park Ave in the high-end residential boom soaring over Central Park. In these residential structures, great value is placed on views, heightening the importance of the performance and aesthetics of the building facade. Additionally, higher winds, congested sites, delivery of units into the city, all are reasons that point to the prefabricated unitized curtainwall.

Keeping up with Schedule Demands

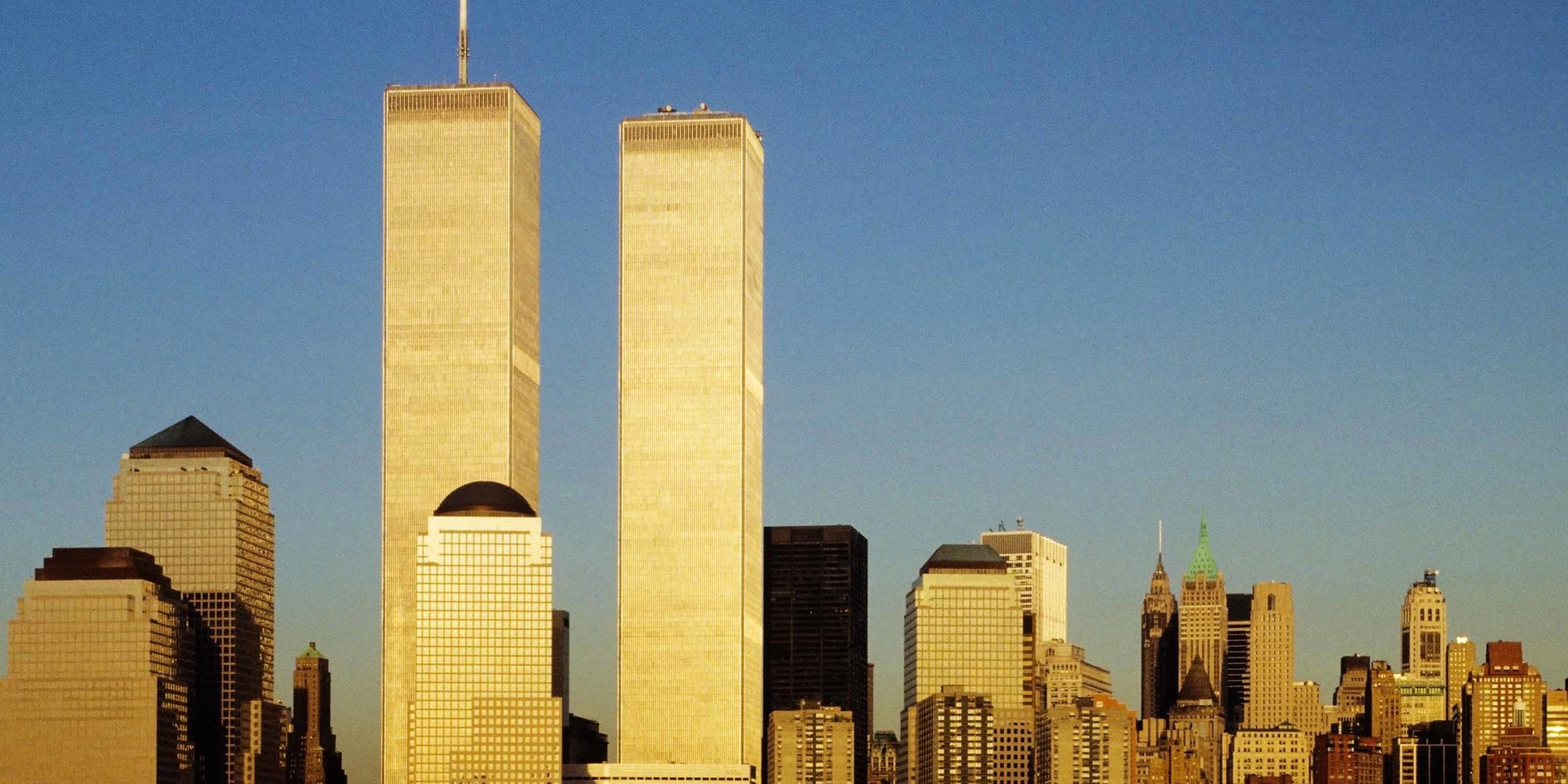

In recent years the number of supertall buildings has increased exponentially, and nowhere in the United States is this more evident than in New York City. The growth has truly been a mix of commercial and residential projects, driven in large part by developers’ desire to provide unparalleled views for luxury condo developments. That trend meshes with Enclos’ expertise in prefabrication, which is at the core of our business model. With dense urban sites, limited footprints, and aggressive construction schedules, prefabricated unitized curtain wall enclosure systems make a lot of sense.

Enclos “did whatever it took. They erected panels 24 hours a day, with excellent and performance-tested quality results”

James McKenna, President at Hunter Roberts in ENR New York1

Curtainwall units are glazed and assembled off-site in a controlled environment, then scheduled for just-in-time delivery whenever possible. The prefabricated curtainwall units use interlocking details that reduce field activities such as applying joint sealants. This approach allows for manufacturing to build-up a backlog of prefabricated units off-site so that – when the site and primary structure are ready – facade installation crews may hit the ground running, sequentially wrapping the building a floor at a time from the bottom up.

Vertical Mobility

To meet project schedules, identifying how units will elevate to their final location on the building is an essential challenge to resolve early. On project sites, a hoist is used to transport crew members and materials vertically throughout the building. It is common for facade contractors to use the hoist to lift bunks – crates or racks of several units – to their respective floors for uncrating and preparation for installation. This approach commonly uses installation equipment that is fairly mobile and is relocated up the building as it rises. Additionally, this approach of floor loading and setting does not require the use of a project’s tower crane, a high-demand piece of equipment that is as impressive as the structure it erects during construction. The tower crane, or cranes for many mega projects, is a highly-sought-after resource for many trades.