by Earl Patrick, Enclos Director of Design

Enclos is proud to have provided the facade for the recently completed new Embassy of Australia at 1601 Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, D.C. Designed by the Australian architecture firm Bates Smart, it replaced the previous modernist embassy also designed by Bates Smart, which opened its doors in 1969. For the new chancery, which opened in August of 2023, the major feature of the facade is its copper panels, which are meant to evoke the colors present in the Australian landscape found in places such as the large sandstone formation named Uluru (also known as Ayers Rock).

Phase 1 – Chasing Dollars

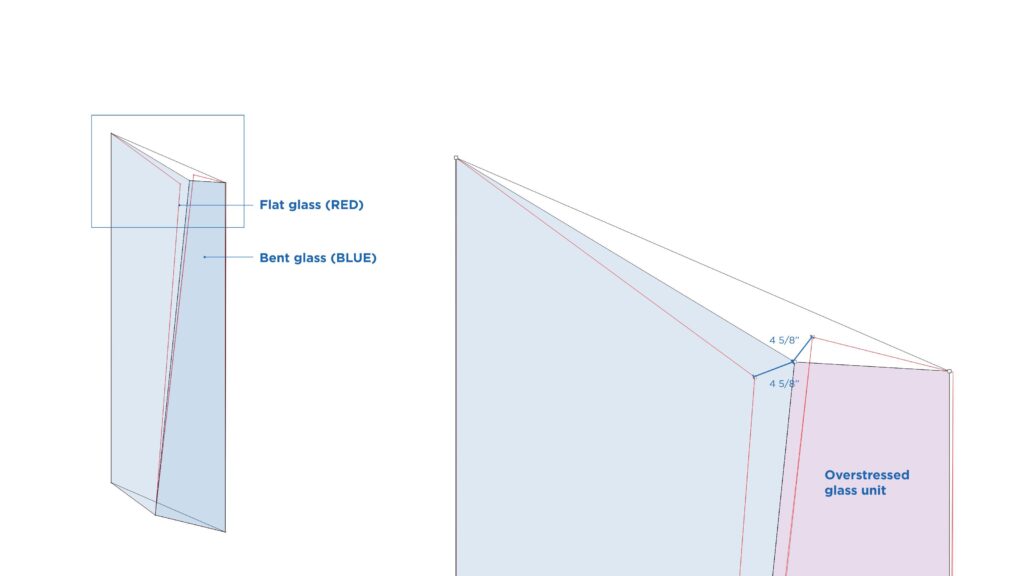

The initial architectural design for the main exterior facade presented a challenging curtainwall unit typology. Bates Smart’s original concept had the glass units projecting from the structure and meeting the copper panels at an apex away from the edge of slab by as much as 25 inches (Figure 1). In addition, the joints between copper and glass were not planar due to the nature of the proposed facade geometry, and this resulted in glass units that would have been warped out of plane beyond the limits of cold bending (Figure 2). These two features of the curtainwall unit typology, in combination with the premium for the copper alloy panels, caused the initial pricing estimates for the facade to come in well above the proposed budget. In the summer of 2018, five years before the building would be completed and turned over to the Australian Government, Enclos was engaged directly by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and asked to help Bates Smart craft a facade that still met the design intent while being within the budget allocated for the project.

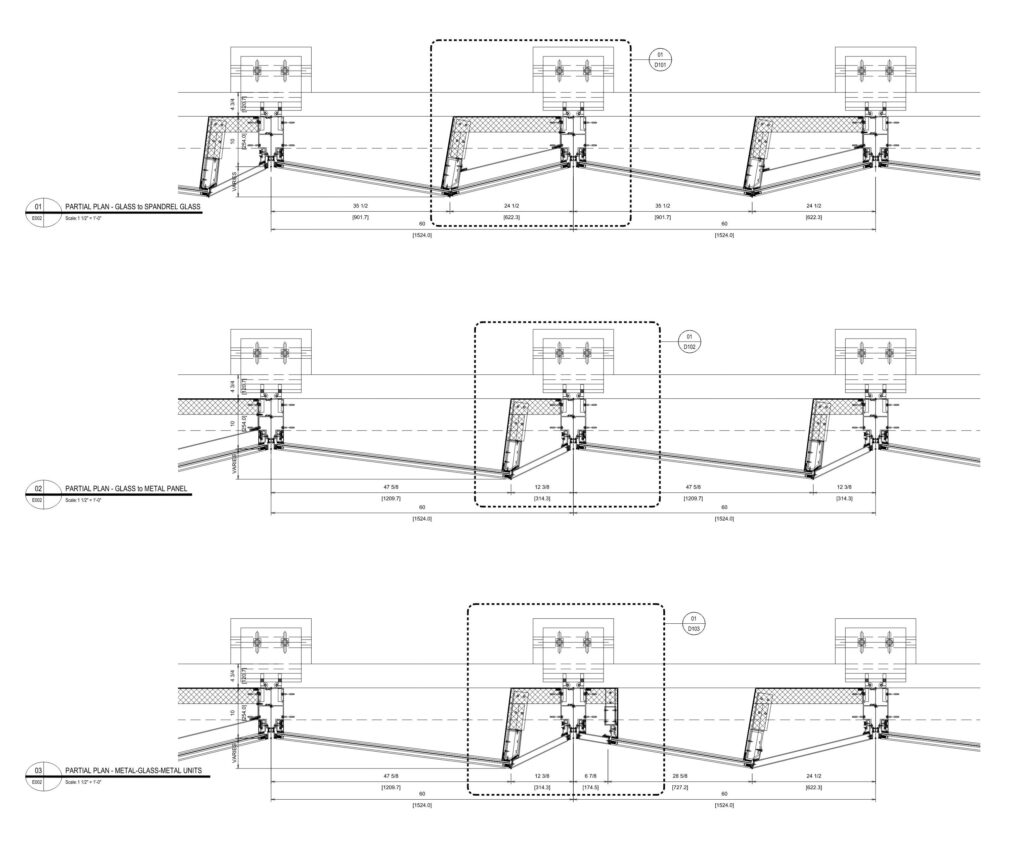

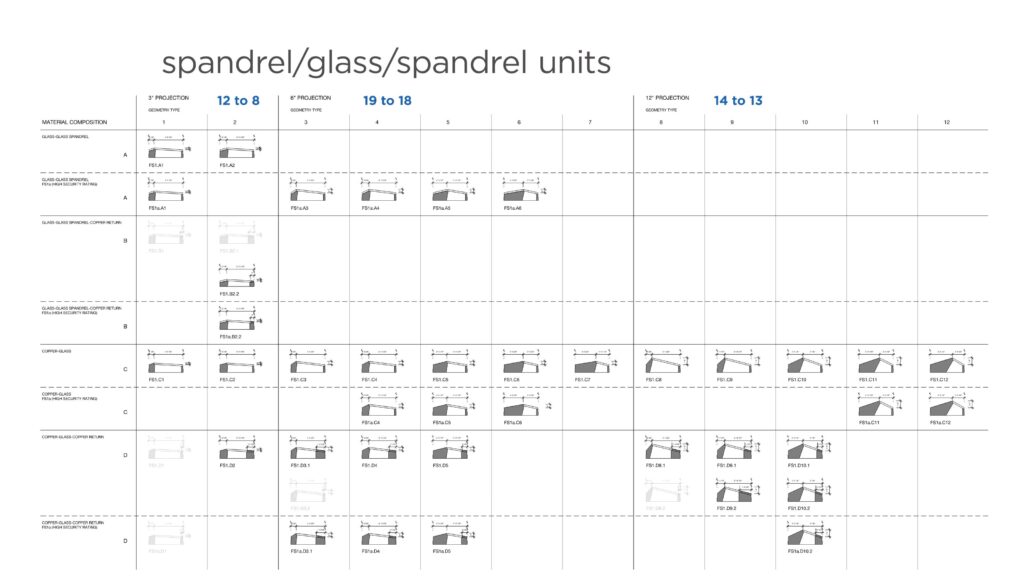

Given a dictum that the copper panels were integral to the spirit of the project, the initial strategies Enclos employed for cost reduction were aimed at making a minimal impact on the design intent given by Bates Smart. Firstly, Enclos suggested reducing the number of the unique unit types by combining units with similar materiality layouts (within a 6” difference in spandrel width) (Figure 3) and reducing the projection of the apexes of the most extreme trapezoidal units from 25 inches from the face of slab to 22 inches. In addition, studies were conducted to rationalize the sloping apexes of the curtainwall frames to produce topography to the facade, which would require only flat or minimally cold bent glass units. Once completed, costing models were rerun, and the attendant figures were provided to DFAT. Unfortunately, the facade was still over the budget set by the Australian Government.

By January 2019, it was clear that something more radical would be required in the value engineering of the facade. The initial optimization had resulted in a disappointing flattening of the topography while failing to reduce the costs to get within the budget. Working closely with design architect Bates Smart, Enclos developed an exponentially simpler alternate curtainwall system typology, which kept the glass units and the curtainwall framing flat and rectilinear while putting all the topographical expression of the facade into the copper panels integrated into the unitized system. This did two things simultaneously. First, it brought the cost and complexity of the facade engineering down dramatically while reducing the square footage of glass and eliminating the warping of the IGUs required by the initial design. Secondly, that reduction in cost and complexity was significant enough that it allowed Bates Smart to regain depth in the topographical expressions and produce more unique widths and depths of the folded copper panels, essentially undoing some of the previous rationalizations of the optimized base design. Enclos provided multiple full building renderings of design iterations and potential panel layouts to Bates Smart and DFAT, ensuring no surprises in the completed facade. After six months of close collaboration between Enclos, Bates Smart, and Washington D.C.-based architect-of-record KCCT, the outcome was a reduction of 23% from the base bid cost of the facade and an alternate design that held close to the spirit of the original facade concept (Images 3, 4 & 5).

Phase 2 – Chasing Copper

The copper panels on the Australian Embassy were originally envisioned with a highly organic and non-uniform finish made by applying a flame and burnishing the material to discolor it, producing an effect some described as having rainbow-like reflections – like gasoline when it floats on water. This finish must be protected from typical copper patination by overcoating it with a clear lacquer or poly-type finish. Bates Smart had been engaged in a research and design effort with a panel manufacturer and had produced small samples of copper material with a finish they wished to attempt to spread across the entire scope of the project (Image 6).

During further discussions with the panel manufacturer who provided the sample, the design team discovered there were concerns about producing the volume of material needed for the building in the timeline the project required. The full project would need nearly 760 panels in approximately 350 unique shapes, ranging from 26 to 80 inches wide and 105 to 282 inches tall. In addition to the scope, there were concerns about controlling the color range of the non-uniform finish. After many trial rounds on full-size material and several visits to multiple panel manufacturers during the project’s design-assist phase, the decision was made to forgo the flame-burnished finish in favor of panels made from coils of mill-finished copper. In part, unfortunately, this decision also stemmed from the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in March of 2020 and the sudden near impossibility of continuing the R&D process with shop visits to panel manufacturers around the globe.

Ultimately, these mill-finished panels would be clear coated with a protective polyurethane lacquer product called Durodur 3057-20089 Clear S-Mat (satin matte) and coated a second time on top of that with a clear wax; Collinite No. 885 Heavy Duty Fleet Wax (marine paste wax). The goal of this two-coat finish was to preserve the copper’s mill color for as long as possible and to avoid the discoloration of copper, known as patination. Copper’s patina color will vary depending on the availability of carbon dioxide and water in the air, and the city the material is in can influence this availability. Larger cities have more aerosol sulfates, which are produced by burning fossil fuels, and this tends to turn the copper oxide a dark shade of green. In the metro area of Washington, D.C., the concern was that the copper panels, if left unprotected, would eventually patinate to a dark shade of brown.

In addition to preserving the color, the copper panels required careful isolation from the aluminum framing of the curtainwall to prevent galvanic corrosion of the aluminum unit framing itself. To this end, a chassis of stainless-steel shapes was used to mount the panels and separate them from the curtainwall framing. These stainless-steel sub-assemblies were mounted on the curtainwall frames by one of Enclos’s vendors near Bangkok, Thailand. The completed units were then sent to a staging yard near the job site before making the final trip to the project site for a just-in-time delivery before setting.

Once the units were on site, the copper panels were installed onto the integrated stainless-steel frames before the units were lifted into place on the building structure. This “drop shipping” of the copper panels to the job site allowed for minimal handling of the noble metal and meant that the topography of the units was reduced for more efficiency in packaging and shipping.

Phase 3: Chasing the Startline

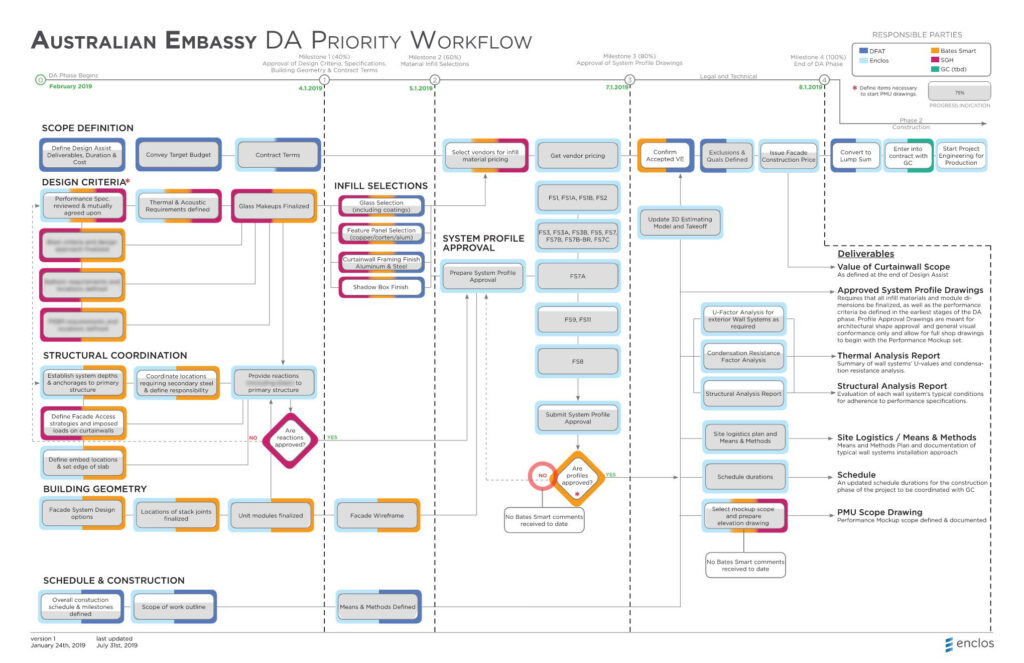

The design-assist phase, of course, had to answer many more questions than just the finish of the copper material, as critical as that was. To transition into production engineering by August 2019, it was imperative to focus on multiple fronts. These included definitions of scope, design criteria, structural coordination, thermal and acoustic coordination as well as defining the final building geometry. In addition, there were also other infill materials to select, not the least of which was the glass – including its coatings and the supplier. Paint finishes also needed to be selected for the framing and the shadowbox panels. All these varying inputs and constraints applied not only to the primary exterior facade but also affected the several other facade system types on the building, including a dramatic light well and attendant interior courtyard.

With so many variables to keep track of during a design-assist phase, Enclos has come to rely on a unique tool we create in collaboration with other members of the design team. Referred to as a priority workflow, it is a graphical representation of required design decisions laid out sequentially against a backdrop of the design-assist phase timeline. Key players for each decision are identified by color, and those colors are assigned to items in the workflow so that all parties know what they are responsible for coordinating. Milestone dates separate major inflection points in the process, and it all ultimately leads toward a set of defined deliverables. For the Embassy of Australia, those deliverables included:

- The final value of the curtainwall scope

- Approved system profile drawings

- A full thermal analysis and report

- A full structural analysis and report

- A documented site logistics plan and attendant means & methods

- A project schedule

- Defined and documented scope for the Performance Mockup

The included priority workflow for the New Australian Embassy (Figure 4) reflects all that goes into a monumental building before the project engineering has begun and long before the material reaches Enclos’ shops or the final unit assemblies arrive on site. As we look back on the now-completed Embassy, it’s with great pride that we reflect on the hard work of the entire project team during this early design collaboration phase, look at the original renderings, and compare them to photos of the now-completed chancery.

All photos by RON BLUNT, unless otherwise noted.